For decades, Pakistani dramas have used the joint family setup as their favorite playground—especially in Ramzan comedies that turned domestic chaos into primetime laughs. The mothers-in-law evolved from scheming matriarchs to endearing Shahanas, and the heroes transformed from toxic husbands to progressive, tea-brewing men. The formula worked—Gen Z found this updated version palatable, even “cute.”

But beneath all the banter and chai-making, one truth persisted: the joint family system wasn’t going anywhere. It was still glorified as the symbol of our cultural roots, a sign of unity and respect. A big win, right?

Well, not quite.

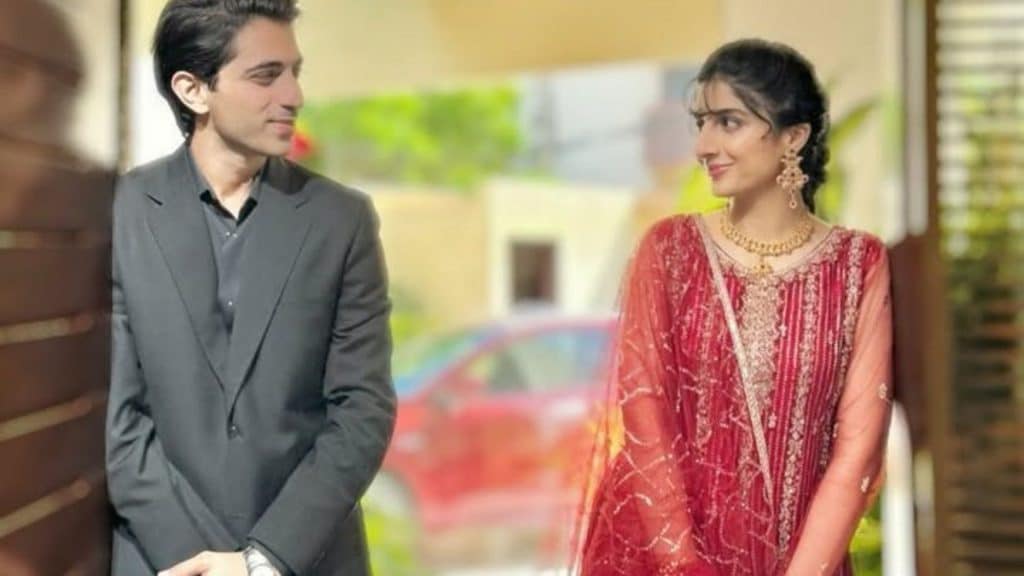

Enter Jama Taqseem—a drama that holds up a mirror to this supposedly “wholesome” setup. Featuring Mawra Hocane as Laila and Talha Chahour as Qais, it has sparked a collective catharsis among viewers. For the first time, audiences are seeing the cracks in the wall—moments of quiet harassment and control masked as love and tradition.

Viewers aren’t just watching; they’re relating. Imagine a young bahu sitting beside her mother-in-law as Laila is scolded for visiting her own mother without permission, or when Qais sneaks sushi into their room because sharing it with the family would raise eyebrows. It’s funny—until you realize this is how many actually live.

Pakistani dramas have long used humour to soften harsh realities, turning pain into punchlines. But Jama Taqseem exposes how that “toxic positivity” has normalized emotional suffocation. When a woman is expected to cook, clean, and seek permission to leave the house, what else can we call it but harassment?

Laila’s story hits hard because she sees what others can’t—or won’t. “People who live with a smell around them can’t notice it,” she says, describing a family blind to its own toxicity. Qais, used to the system, sees nothing wrong. The metaphor stings, because it’s true: the dysfunction is invisible to those who’ve lived in it too long.

Not every woman in the drama reacts the same way. Laila chooses defiance; Nighat, armed with privilege, bends the rules; Rashida, powerless and burdened, suffers in silence. Through them, Jama Taqseem captures the hierarchy of pain in the joint family setup—the strong survive, the weak endure, and everyone calls it love.

So, is Jama Taqseem exaggerating for effect, or finally telling it like it is? Either way, it’s a bold step away from the rose-tinted portrayal of family life we’ve been fed for years. It doesn’t romanticize the joint family—it questions why we ever did.